This summer, I hosted textile-blood-bag-making workshops in Seoul and Kyoto with Leigh Bowser, the founder of the Blood Bag Project. Leigh started the project to support her niece Chloe, who suffered from a rare blood condition called Diamond Blackfan Anaemia. Coming across Leigh’s work in 2021, I became fascinated with Leigh’s use of craft in creating dialogues and connections around blood. Leigh’s textile blood bags made tangible the intentions and interconnectedness of their makers, creating their own circulations alongside the circuits of biomedical blood bags. I have since invited Leigh to speak at the Hematopolitics Symposium and co-hosted a workshop for Year 6 students at a local primary school. These experiences led us to consider the potential of blood bag workshops in bringing together blood donors, patients, and supporters in my field sites in Korea and Japan. Coordinating with our collaborators in Seoul (Korea Leukemia Patients Organization) and Kyoto (Prof. Toyoko Kōzai, Bukkyō University), we were able to co-host workshops in both locations with a programme redesigned for each occasion. It was Leigh’s first time to host blood bag workshops outside of the UK. Below is Leigh’s reflection on the encounters (Jieun Kim).

Before the Trip

Before making the trip to Seoul and Kyoto, Jini (Dr Jieun Kim) and I worked on putting together as much useful information as possible for participants. This included a schedule for the workshop, breaking it down into sections of time to assure participants had enough time needed to make their bags. Photographs of the available materials and examples of other bags helped to give them inspiration. Jini translated these into Korean and Japanese ahead of time.

We agreed that a specially made label with space for the makers to include any text they wanted would be useful. It would also serve as a way of documenting who made each bag, and which workshop it had been made in. We agreed upon a label which would mimic the stickers found on blood bags, with a name, location and faux bar codes for authenticity. After working together to get the design right, I created a printing screen at Leeds Print Workshop and hand screen printed each individual label onto calico. Once dry and heat pressed, they were overlocked but hand using my overlocker sewing machine. 40 labels were made in total to allow for mistakes to happen, both in their printing process and by participants who might change their minds on what they’d like to include.

To make the workshops flow as naturally as possible despite a language barrier, I put together a mini question card which included the most frequently asked questions I receive during stitch-based workshops (e.g. can you help me thread my needle?). With help from Jini, these were translated into Korean and Japanese and printed doubled sided. They were placed inside the information packs given to each participant.

Whilst the language barrier may be a little nerve wracking, I felt confident that my experience of working with people in stitch-based workshops for over 10 years would allow me to support people without too much confusion. My experiences have allowed me to understand the patterns in people’s body language and creative process when stitching to read when they may be struggling and need help. As it is a physical task, demos can be used without words to show how the techniques are achieved (e.g. how to do a stitch can be broken down into simple steps that can be physically shown, rather than verbally described).

Blood Bag Craft Workshop – Seoul – 20th July 2024

Upon arriving at the venue for the workshop, I was greeted by a large standing banner sign specifically made for the workshop. The bright and clear graphic helped me know exactly what it was for before even needing to translate the text. Seeing this made me feel immediately welcomed, as the effort made to create the signage and cost of having it printed meant that those organising had put in a lot of anticipated effort and were enthusiastic about the workshop.

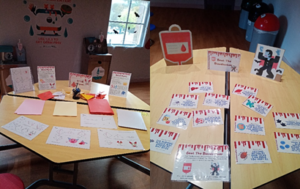

When I entered the space, I was introduced to the KLPO (Korea Leukemia Patients Organization) team, Gi-Jong An and Eun-Young Lee, and their lovely volunteers, all of whom welcomed me and made me feel more relaxed. We worked together to set up, putting out materials, equipment and paperwork, as well as setting up the presentation screen. Jini talked with me about who we would be expecting to participate and the general outline for the flow of the workshop. We had prepped schedule ahead of time, but it was reassuring to go over this again.

The participants began arriving (around 17 people) and settling into their prearrange seats – KLPO did a brilliant job of sitting people together in a way that would help them connect with one another, such as putting families with young children together etc. This worked particularly well for three young men who were all first-time participants in a KLPO event and had each come alone. This common experience was enough for them to begin bonding. Throughout the workshop, they got to know one another a little more and shared similarities of interests, such as music.

Once most of the guests had arrived Eun-Young Lee introduced the workshop and shared her first-hand experiences and in particular the reason for setting up KLPO. The microphone was then passed around to allow participants to introduce themselves and share a little about their stories in relation to Leukaemia. Jini kindly translated these stories to me as they were being told. For many, the workshop was their first time participating in a KLPO event or meeting other people with similar experiences as them (e.g going through, or supporting family members through, Leukaemia treatment). Many expressed being nervous about attending, but were looking forward to making connections with others. Some spoke about difficult moments in the treatment of either themselves or their young children, which the others members of the group were understanding and empathetic of. I am very grateful to every person who shared their story.

Cho, one of the three young men sat together, seemed to be the most confident in sharing his story which allowed the others to relax and share their stories too. He was very enthusiastic about his design, which showed many hands touching the same heart in the centre of the bag. This was to symbolise all the different people who had helped him throughout his treatment, including those who donated blood. Whilst he was a little unsure of his sewing skills, his excitement for his piece allowed him to put together in a way that he was happy with. He was brilliant at passing this enthusiasm onto the others around him, gathering people together for photographs and encouraging them show off their own bags too. During the workshop, Cho expressed his gratitude for KLPO bringing everyone together and found it hard to express how it made him feel – he described it as his heart was full and it was a feeling he would take home with him. I am very grateful to Cho for his open, friendly and enthusiastic participation. Cho shared his experience on social media: https://www.instagram.com/p/C9pPCY1z3Ks/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

The pre-made translation cards came in very useful during the workshop and helped me understand the needs of the participants. I also try to pre-empt questions by watching people work. For example, if someone is trying to thread their needle, I usually allow them a few attempts themselves before offering help – sometimes they’re able to get it themselves on the third or fourth attempt and this helps them become more confident in their skills, rather than relying on me to do it for them every time. The volunteers were also brilliant at supporting participants and myself throughout the workshop. If someone required support whilst I was helping someone else, they would try their best to help first and would then ask me directly if continued support was needed. This was done both verbally, through the communication cards, and by making understandable hand gesture such as holding up needles and threads.

The benefit of a physical, in person workshop was most obvious to me when working with two children, aged 6 and 8. Neither had done any sewing before or spoke any English (and my Korean is limited to hello and thank you!). However, by showing them both step by step how to construct their bags, they were both able to draw, cut and stitch their ideas together. They were both very patient and determined.

Some worked together as family units to produce one bag that reflected their experiences. This included a mother and child working on a design of a ladybird, who represented the child’s favourite hero character Miraculous Ladybug, who is watched by children all over the world, including in the UK and South Korea. This well-known character is another example of how connections can be made globally without the need for verbal communication, as fans of the character have an instant association to the piece. Characters played an important role in a few of the designs – another family used a blue character that had visited the hospital and become a ‘friend’ to a child who was isolated by their treatment and experiences from others their age. This cute and cuddly character had made them feel happy and loved to see them. Characterisation of sometimes scary experiences into something softer, cute and lovable can help people, especially young children, to cope. This is something I have investigated through my own telling of Chloe’s story and will be explored further by Jini and I in the future.

A few days after the workshop, I received three links to exciting videos and write ups. One in particular came directly from participant Kim-Dan-Young:

https://youtu.be/3NCE04eeAv4?si=1AUQkuKThrhokcCo

Kim-Dan-Young was a keen crafter and Youtuber before her illness. She lost her extremities during her harsh leukaemia treatment and told us she was using that day’s workshop to relaunch the crafting side of her channel. Her YouTube shows love for her new hands and the things she is still able to do, including craft, sometimes with extra support from her husband. Again, the anticipation and forethought from Kim-Dan-Young to document her process and the event helped me to understand the importance of it to her, as she had obviously thought about it a lot leading up to it. I am very grateful to Kim-Dan-Young for sharing with us on the day, but also continuing to share this through her social media.

The same can be said for KLPO, who had their own videographer and photographer at the event to capture the workshop:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=kIJqYTGzRLs&feature=youtu.be

An interview was conducted at the end with Jini and myself to help us reflect on how it had gone. This footage was then used as an informative YouTube video to share the project and Jini’s research. I was asked if the workshop in South Korea was different to the ones I hold in the UK – I did not feel that there was any difference culturally or that the language barriers prevented the workshop from being the best it could be. The biggest difference had been the participants themselves – their firsthand experiences made the workshop a more empathetic and understanding place and allowed people to connect more deeply through their shared experiences of difficult medical experiences.

The day was also featured on Hit News, a medical website in South Korea:

http://www.hitnews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=56277

Blood Bag Craft Workshop – Kyoto – 3rd August 2024

The second workshop was held at Bukkyo University’s Nijo Campus and was put together with help from Professor Kozai. Professor Kozai had recruited students and friends to join the workshop, some of whom had connections with blood donation, but most of whom did not. After setting up, the 8 participants arrived and introductions were made. Most of the students expressed their reason for attending being that they had a lot of respect for the Professor and were keen to learn something new. One student said a friend of theirs had to have regular blood transfusions, so they had been inspired by them to attend to learn more. This has been the more frequent and usual path of participants in blood bag project workshops in the past, with people keen to learn a new skill such as embroidery, want to learn more about Diamond Blackfan Anaemia and blood donation or get involved because they know someone who has received a blood transfusion.

As the participants began creating their designs, a common theme amongst the makers was that they wanted to spread hope and joy. Again, characters and characterisation became a way of doing this, by adding smiling faces to shapes to give them cheerful personalities. Hearts and hands were also heavily featured across both workshops, icons that span most cultures as symbols of human connection, love and happiness.

Whilst I enjoyed delivering this workshop, it felt like participants were a little more apprehensive than in Seoul. I find this is not unusual in workshops in which participants may find it harder to find common ground if they do not already have personal connections to the topic. Nervousness of working with unfamiliar people can also make participants a little more hesitant. Nevertheless, they all worked hard to complete their textiles pieces on the day. The two youngest members, who were around 9-11 years old, seemed to have the most confidence in their ideas and were most open to talking to us about the project. Through working with children on The Blood Bag Project, I have found that the younger they are, the more confident they are with their ideas and are less concerned about if they are ‘good enough’, and so are able to more fully invest themselves in what they are creating. Unless you work in a creative field, adults are often given less ‘permission’ to be creatively free on a regular basis, which can then add to nerves when they are.

Overall Reflection

The whole experience is something I will remember and be appreciative of for a very long time. The open, honest and vulnerable sharing of stories, particularly at the Seoul workshop, was an experience I will always be extremely grateful for. Whilst most workshops I run based on Blood Bags are similar to that of the Kyoto workshop (i.e., people learning about blood donation and reasons people might receive transfusions), the KLPO workshop showed me first-hand the importance of working directly with patient groups; that people need to make connections with others who understand them and the things they have been through, and that the craft was just a small part of the vehicle for this sharing. Being able to connect with people through craft is the reason I love the work that I do. Doing this with groups of people who speak another language and have different experiences to me have proven this to me even more, as it demonstrated to me first hand that craft, and in this particular case textiles, can connect people despite a range of barriers (Author: Leigh Bowser).